by Jonathan van Geuns, June 22, 2025

Snowdonia does not welcome you gently. It rises suddenly, dark and wet, and unbothered. Its ridgelines serrated like old teeth, and its paths more suggestion than route. The mountains don’t tower, they brood over you. They don’t gesture for attention, yet they hold it, in silence. The land feels older than memory, held together by slate, sleet, and a lot of something else. The same land carries the mark of industry and resistance. It roofed cities and housed the largest quarries on Earth. You still see the bones everywhere, jagged piles of waste, rusted winches, stone ruins.

In the heart of Eryri, the Welsh name for Snowdonia, where the mountains rise like ancient sentinels and the skies often weep, I found my initiation into this world of trail and ultra running. I didn’t go looking for it. But something in the land found me first. I came to know it by accident. The best advertisement one could imagine. Little did I know, the Ultra-Trail Snowdonia (UTS) 100 wouldn’t be just a race for me; it would become my rite of passage, forging my identity, as both human and runner. Across multiple years, I’ve returned here, not just to race, but to understand what this place keeps teaching, and what it’s slowly forgetting.

What follows here is long. This isn’t a travelogue, nor is it really a race report per se. An account of running the UTS 100, yes, but also of returning to it, being shaped by it, watching it shift as races and landscapes do. This read is for those who have run it, and might recognize the turns. It’s also for those who are drawn to the idea that a race can be more than a challenge. And hopefully also for those who take pleasure in losing themselves in the lands of Tolkien and fantasy.

Mostly, it’s about a question you keep returning to; an attempt to name something that has no easy way of saying. The longing for a place that may never have fully been, and the refusal to let it go. It isn’t nostalgia, it isn’t longing, or homesickness. It isn’t about recovery. It is a feeling for something that may never have fully been, but which still holds you. So forgive the sprawl of this telling. Like Eryri, it doesn’t unfold neatly, it’s meant to be wandered, not wrapped up.

This piece asks a lot. Of your attention, patience, willingness to slow down. It doesn’t offer quick takeaways or tidy resolutions. It meanders, circles back, insists. That has become part of the point. Like Eryri, it’s not meant to be rushed through or skimmed. It’s meant to be felt, wandered, wrestled with. For those willing to stay with it, it might offer something rare: a way of remembering what matters; place, effort, change, and the quiet ache of belonging. I hope it’s worth the weight.

Eryri isn’t just the Welsh name for Snowdonia; it’s the rightful one. I believe it means “place of eagles.” Many of the peaks still carry names you have to learn phonetically: Moelwyn Mawr, Tryfan, Pen yr Ole Wen, and of course Yr Wyddfa. You’ll rarely see eagles now, but the language holds the memories.

Michael Jones, the Welsh runner behind the race, with proper pedigree in races like UTMB, took his experiences home with him. Every section of the route was made deliberate, as if he’d passed it thinking: “We need this too to either break or build you.” Mike wasn’t just trying to create a hard race. He wanted to bring something to the UK that hadn’t existed before: a true Alpine type of an ultra. He got what he wanted.

The terrain of Eryri resists classification. It’s not Alpine in the classic sense—there are no glaciers, no soaring limestone cathedrals—but what it lacks in straight elevation, it makes up for in sheer toughness. The climbs are steep and direct, and can still cover a 1000m, especially when accounting for the false summits. The descents are loose and jarring. The trails, when they exist, are often submerged in water, or lose rock, or disguised as sheep tracks. You learn to read the ground with your ankles. It’s the texture of the land that wears you down. Slippery rocks that move underfoot. Sections that suck your shoes off. Running here isn’t just physical. It’s something else.

I’d never set foo in Eryri. For six months I’d lingered in London’s grey sprawl, far from any place that breathed like the mountains do. Something in me stirred at the name of Snowdonia. Something in me reached for that land. I wanted in. I had enough spark to contact Mike, knowing full well I lacked the credentials. Since I didn’t meet the experience requirements, I’d show him what I could do; hunger, heart, the promise of effort unmeasured might count for something?

The idea of this race felt like a door I hadn’t walked through yet. We agreed on two long solo runs, the tracks shared as proof. The pieces came together like moss and stone: Ana was away for work and though the hostel in Llanberis had shuttered for the season, they graciously let me in, quietly, I was welcomed into the hush of January.

I had meant to cover fifty miles in two days. Get a feel for the terrain. See what my body could manage. The mountain had other designs. That plan dissolved rapidly. Instead, I found myself doing repeats up Snowdon, five times, following the curve of the Llanberis path. Snow began to fall as I reached the summit for the first time; in fact my first true mountain summit (ever). The wind rose to meet me, fierce and full of song, and I stood in its judgment. Below, the Pyg Track, its rocky descent shone with ice and shadow, slick and jagged. I knew then my feet would not find trust there. Completely alone, unsure, I had no appetite for finding out how a mountain rescue works. Clearly the mountain did not care about my plans.

Still, the mountain gave me what I hadn’t known to seek. I passed a few lone walkers with hardened eyes, and an ease that comes from knowing this land. A dog or two trotting beside, as if this were no more extraordinary than the local park. For all its bleakness and heft, Eryri flips the switch. The sky breaks open, and the whole range lights up in gold. The slate catches fire, the bogs gleam, the peaks rise as blades etched against a clearing sky. For those fifteen minutes, maybe, I understood now why people keep coming here. It is the air, knife-clean, edged with weather. Water everywhere, pouring, trickling, murmuring in stone, dripping from moss, braided into the roots of it all. The scent of sheep hanging in the wind: musky, sour, oddly grounding. I stumbled onto an indifferent world. Yet, I’d rarely felt more present. Invigorated, more alive, more at home.

There’s no universal rule for what makes a mountain a mountain. Not really. Not even in Wales. Some lists define it as anything over 2,000 feet, or 610 metres. Others demand a certain prominence; 30 metres, 150, even 600 for the so-called “Majors.” There are Simms, Hewitts, Marilyns, HuMPs, and P600s, each with its own bureaucratic threshold. But in Eryri, none of that quite fits. Here, a mountain isn’t measured by contour lines alone; it’s defined by how much effort it asks of you. A hill you climb. But a mountain holds you. It makes you listen, reconsider. You feel it in your chest, in your decisions. While officialdom might say 600 metres is the legal threshold, that’s not enough here. In Eryri, a mountain is something that changes you. Something that names you back. Sometimes, something that names you wrong.

2018: “The Inaugural Year”

You rarely grasp the scale of the story you’ve stepped into until much later. Like the hobbits setting out from the Shire, it begins as something intimate, quaint; just a hard run in a wild place. You pack your gear like its second breakfasts: a touch too much, too heavy, a touch too hopeful. Embarking on my first 100-miler with only a few months of training was audacious, and likely a form of quiet arrogance. I stood at the starting line, naively confident. Eryri, indifferent to my inexperience, unaware of the shape of the trial ahead, ready to test my mettle.

The race began as the heavens opened, baptizing us in a slow downpour with an old, familiar grace, surprising no one. As though the land itself were welcoming us in its native tongue. The Welsh language has no single word for “good weather,” but there are dozens for rain, for mist, for the many moods of cloud. You could feel the collective sigh before the gun went off. The only time I’d been here before was during the grim winter months. The rain felt soothing.

Eryri is a land shaped by water. It is one of the wettest places in the UK, with nearly 180 inches of annual rainfall, more than double Seattle’s tally. Crib Goch, the notorious ridge, a few kilometers from the start line, holds the national record. The sky in here is rarely still. Clouds roll through like freight trains. Mist clings to the slopes like breath on glass. Sleet arrives uninvited. Rain is the house guest that never leaves. Sun, when it appears, is a blessing. You don’t train for the weather here. You make peace with it.

Back then, I charged every course from the outset. I didn’t understand pacing. Effort was pretty much the only lever that mattered. So I surged up Yr Wyddfa, Welsh for Snowdon, in third. It rises 1,085 meters, from sea level. The Llanberis Path is deceptive, as it is mostly gradual. It can hit hard when your ego hasn’t checked itself. Same for the Pyg Track, which I attacked borderline reckless. Still, I was passed by a seasoned, Fremen-like, mountain-born. The descent is exposed, technical, and sharp, like many in Eryri. Like a young off-worlder stepping into the sands without learning the desert’s rhythm, I moved, relying on luck over technique. If I’d fallen, I would’ve gone a long way. But I didn’t.

In the winter before their historic Everest ascent, Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay trained nearby, using the Pen-y-Gwryd Hotel as their base. On the icy slopes of Yr Wyddfa and the Glyderau, they tested gear, practiced climbs, and readied themselves with wool, grit, and silence. The hotel still stands today, with their names scrawled on the dining room ceiling; ghosts of ambition and humility etched into the wood, reminders that even the world’s highest dreams can begin in the wet winds of Wales.

Dolwyddelan came just before the dusk swallowed the last colors from the trail. One runner slid by; another, drifted in the opposite direction, looking empty, spent by effort he’d borrowed too early. I crossed with Marcis Gubats, the calm Latvian, and previous Lakeland 100 runner-up (behind Mike himself). I hadn’t expected to see him then, departing as I arrived. A missed turn had forced him to double back (he would go on to win the race). The guys in 2nd and 3rd did not. For a breathless moment, I wondered: would it matter? Would the missed stop catch them out? Was I, now, in second?

I reached Dolwyddelan before the light gave out. A runner slipped past me; another, drifting in the opposite direction, looked emptied, spent by effort he’d borrowed too early. I crossed with Marcis Gubats, the calm Latvian, and previous Lakeland 100 runner-up (behind Mike himself). I was surprised to see him leaving the aid station just as I got there. He’d missed the turn, and had to double back. The guys in second and third did not. For a moment, I wondered: would it matter? Would the missed stop catch them out? Was I, now, in second? Was I competing now?

As the trail bent toward Capel Curig, the forest grew thicker toward, and the clear smell of the earth breathing up its rot. The deep, loamy musk of humus and decay. Fungi clung to every surface: fly agaric, bright and angry in the moss; birch polypore, pale as old skin; and mycena, trembling like something half-alive. Even the living trees bore them. Nothing wasted here.

Capel Curig lies in the heart of everything and nowhere. A village that behaves like a trailhead, a junction more than a destination. But it’s been a center of outdoor life in Eryri for decades. The Plas y Brenin National Outdoor Centre is here; the UK’s leading training ground for mountain leaders, climbers, and winter survival experts. That heritage adds a quiet gravity to the place.

The path continues while the forest gave way to ruin, bruised earth, the felled trees and forgotten, leaving stumps like the bones of something older. Nearing the Llyn Cowlyd reservoir, through fields of heather, I veered off course and found myself chest-deep in cold black bog (I’m 6’3” or 190 cm). There was no panic, just half a laugh, half in disbelief. Past the dam, besides a concrete shelter, a single volunteer stood with a few jugs of water, and modest offerings. It wasn’t an aid station so much as a quiet proof that someone remembered we’d be coming through. With the cold and wind setting in, not a place to linger. I probably should have.

Eryri doesn’t feel like untouched nature. Eryri bears the weight of ages. Eryri is a land sung into being and scarred by its stewards, where the wind carries the sorrow of slate quarried and forests felled. The hills aren’t shy about what they’ve been through; used, discarded, and allowed to regrow on its own terms. Marked by hands now gone and wounds now mossed over. You see it in the stone husks of engine houses, in the slate fences zigzagging over ridgelines, in the flat-topped mounds of waste rock that have become accidental cairns. All here is aftermath, the remaining trees are second-generation. Run long enough here and you start to understand this isn’t mere ruin nor wilderness, it’s memory.

The Carneddau, the Cairns, is a series of peaks both majestic and merciless. A vast, brooding spine of some long-slain giant, stonebound and slumbering in north Wales. With its six-seven summits, is a relentless test of endurance. Few outside Cymru know their names, but they should. They’re massive, open, exposed. Flat boulder-strewn plateaus. Treeless, bare, elemental, they stretch in long, unforgiving windswept halls of stone and sky. Each summit has its own voice and demands its own negotiation, like the sketchy scrambles of Craig yr Ysfa. There’s often no trail to follow, just intuition and the occasional cairn.

They rise like Tolkien’s Misty Mountains, silent witnesses to old wars and older weathers, their peaks unreadable except by those who have bled upon them. I reach for Tolkien because his landscapes speak the same language. Most of Eryri remind of the ancient burial grounds in the North Kingdom, known for their hills bereft of trees, and barrows that hold the remains of Dúnedain men. In Eryri, there are no kings, just cairns. But the feeling is the same.

An outcast, Pen Llithrig y Wrach, part only of the inaugural edition, felt spiteful in its obscurity, and cruel as its name, the “slippery peak of the witch.” Just sodden grass, and slanted slithering gradient that leans directly against you. A fellow runner and I lost the line, the hillside offering no hint of correction until a trio of runners with steadier feet set us right. Climbing the Marilyns in daylight during the recce was one thing; to face it at night, with rain turning to sleet, slicing sideways through the dark, and the cold as a a constant companion, this was something else.

There’s a trick Eryri plays on your perception of distance. The mountains do not tower as tall as those in the Alps or the Rockies, but they feel taller. Their posture, an angle of approach, the lack of trees, the constantly shifting weather, that makes each peak seem farther. You crest, thinking the summit near, only to find another beyond it, just the herald of another. That disorientation is part of the challenge.

I ran out of water before reaching Carnedd Llwellyn, Cymru’s second-highest throne of stone. I’d counted the sips, but over six hours on this section required more than the two bottles I had on me. I thought of those still behind me, stretched thin by time and terrain, perhaps with the mercy of daylight but none of ease. On Carnedd Dafydd, I came upon an emergency crew, huddled in a slate-blown shelter, a tent cinched tight against the wind. They saw in my face what I could not voice, and filled one bottle, meant only for the direst need. I continued, took one sip, slipped on a stretch of icy scree, and watched the rest of it pour out onto the rocks.

Welsh, ever attuned to its weather, offers over twenty words for mist and fog. That day I recce’d this stretch, it felt like I passed through all of them. I remember vividly, somewhere between the veils of grey and white, and the scattered debris of the RF511 plane, a figure emerged from the mist. Near, I say, the fog made it so you couldn’t see thirty meters ahead. Atop the ridge a pale silhouette appeared, still as stone. A Carneddau pony. Stocky, weatherworn, short-legged, carved into the land. With calm curiosity it just stood there, gazing me. Judging me? Do you belong here? A poignant reminder of the timelessness of this place.

The Carneddau are Eryri’s quiet giants. They do not rise in spectacle. A continues, rising, relentless unfurling of stone and sky, studded with boulders and wind. On a clear day, one may glimpse the silver curve of the Irish Sea and a faint smudge of Northern Ireland. About 300 semi-feral ponies roam here, older than the oldest tales, maybe since the Bronze Age. Seeing one near a summit feels like stumbling across a secret.

With cold inside my bones, mildly dehydrated, I reached what was not an aid station in the usual sense. I came upon someone’s house, no sigil nor banner of old, but a converted sanctuary offered freely to strangers. They had warmth, soup, and more kindness. I sat there, until I stopped shivering. It took two-three bowls of soup and the promise of sunrise to revive me. My shin pulsed like a drumbeat out of time, swelling quietly, and I wasn’t sure what that meant yet.

Llyn Ogwen rests between the Glyderau and the Carneddau like a sword laid to sleep. Cold and still as a king’s last breath. The path skirts its edge in haste, but the lake lingers, steeped in legend. Some say this is where Arthur cast Excalibur after his final battle. Truth or tale, it’s a place where many memories lay dormant.

The first hints of light gathered at the edges of the sky. Tryfan rose to my right, jagged and improbable; a shark’s tooth lodged in the land, too steep to seem natural, too striking to ignore. Skidding over scree, I was energized by the prospect of seeing the Glyderau in full morning glory. Glyder Fach, Glyder Fawr—gludair, the stone-heaps. Their summits fractured plateaus, slabs thrown skyward, and frozen in collapse, like thrones forged from the swords of vanquished enemies. You don’t run across, you pick your way.

Wayfinding in Eryri is to interpret a dialect of stone. You rarely follow a line. You follow intention. Cairns are unofficial, and occasionally misleading. In clear weather, they blend into the landscape. In thick mist, they’re everything. You scan for them like a lost friend in a crowd. In some sections, these stacks of rocks are the only things keeping you from vanishing.

The rocks of Eryri are not simply old. Not romantic, gentle wear of time or worn-down-old, but violent, subducted, re-erupted, tectonic-old. Volcanic ash and lava flows, twisted, pressed, lifted and re-folded, make up much of its craggy heart. The Glyderau especially are a geologist’s field trip gone feral; ridges of shattered rhyolite, tors like remnants of teeth of beasts long slain.

I made it through Devil’s Kitchen or Twll Du. Legend has it the devil cooked his meals in this cauldron of mist. A cleft in the cliffs where weather swirls and echoes. The same haunted narrowing as Cirith Ungol, the dark pass where Frodo meets Shelob. An omen in stone carved by wind and things long buried. The descent is a scramble down slick stone stairs, water running like veins over rock, every step a test of balance.

Below, the valley opens like a scar, leading into one of the lower aid stations, with perfect vegan lasagna. I remember it clearly, not just because it was delicious, but because of the local fellowship who said all the right words I needed to hear, with benediction. They’d seen enough to understand the quiet fray. It’s in these moments that the grassroots heart of the race beats loudest. What glues together the very, living spirit of the sport.

Regardless, my shin began to swell to twice its normal size. What lay ahead, skirting Dinorwig Quarry, and looping back toward Llanberis, was meant to be runnable. It is. I was ninety minutes late meeting Ana, apologizing. I took time to rest and refuel, determined to continue.

Dinorwig and Penrhyn quarries fed the rooftops of the British Empire, once holding over 3,000 workers, exporting slate across the Atlantic and into Europe. You still run through it, the trails bear the imprint of industry, surrounded by piles not left by nature, but by men with calloused hands and short lifespans. The heaps of rock feel orderly and ruined all at once.

Llanberis is the bookend: you start from, or end at, or midway collapse. Once a hub of industry, thunderous with slate wagons, now softened into cafés and trail shops. The cadence of toil remains. You feel it in the brickwork, the pubs, the way the town doesn’t celebrate your effort so much as it nods at it.

The climb up Moel Elio, “The bare hill of Elio,” feels like a merciful reprieve. Its slopes rolled instead of punched. After the chaos of the Carneddau or the upturned world of the Glyders, it’s softened, grassy ascents, were a break for the ankles and lungs. I found a tempo I’d forgotten, managing to run a four-mile stretch, as I confided to the volunteers at the next aid. They returned to me by informing I was in 5th or 6th place, and close to the group ahead. Perplexed, I heard that most runners dropped out. The mountains, it seemed, had claimed its share.

The stretch over Mynydd Mawr passed swiftly. Just weeks earlier, that same hill taunted; its trailhead hidden, tucked away enough for me. I’d wandered through cow-trampled fields, shoes clotted, making endless arcs across pasture fences and bramble thickets before calling it quits. Now, it unfolded without malice. A gentler heather-filled climb, with Craig y Bera emerging sudden, a cliff face flaring out into sky. The descent of mischievous grass, steep enough to ask for your dignity. I answered with practical surrender: on all “threes.” Sliding like a child with no patience for pride.

Some stretches of the trail cut through planted forest; Sitka spruce lined in grim procession. They grow too fast for this soil, too straight for this land. They don’t shelter. No whispering life beneath their boughs. A film set built by someone who’s never been in a forest. It’s beautiful in its alien, geometric ways. But it’s not wild. And the contrast is striking: leave the forest and suddenly you’re back where things decide for themselves how to grow.

Past the shadowed woods of Beddgelert, I glimpsed two crew members lingering for runners just behind me (in not a sanctioned area for support). A flicker of ego stirred, and with it, a pulse of resolve. Yr Wyddfa ahead, once more. This time by the Ranger’s Path. First, a stretch of private land I had overlooked in my recce, not realizing the route would cut across gated land. I had spent too long searching for a path that wasn’t there.

The climb rolls upward with a quiet relentlessness, not cruel, not kind, just steady. Not the steepest way up. I’d come this way enough times to know where the legs begin to warm into it. Rhythm came easier than expected, this far into the race. The wind, mostly hidden here. Higher up, the world starts to fall away behind you. Rocks give way to other rocks. The earth shedding detail until it resembles the surface of another world.

Overhead a peregrine falcon sketched circles into the dusk. I watched it briefly, then moved forward as summit shelter emerged. I paused again, not in struggle, but in reverence for the sun, fat and gold already beginning its descent. I stood like Frodo on Amon Hen, seeing all I had passed through and all I still carried. My Irish companion arrived some minutes later, without needing to say much, we both took it in. A stillness that doesn’t interrupt the race but deepens it.

The highest mountain in Cymru, Yr Wyddfa means “the burial mound” and is said to be the resting place of Rhita Gawr, a giant who collected the beards of defeated kings. Here, Arthur met him in battle, and Arthur slew him atop the peak. The red dragon on the Welsh flag, too, has roots here; tied to a myth where a red dragon fought a white one beneath Dinas Emrys.

The Rhydd Ddu descent always feels long and fast, this time inviting me into a momentum faster than my legs could probably chase. Kevin and I regrouped at the base. We agreed to tackle the next climb together, neither of us knowing exactly what we were walking into. We only knew the dark was coming. What we didn’t know was how vast it would be.

The land here evokes the dread of Emyn Muil, the rugged hills Frodo and Sam navigated after leaving the Fellowship. Similarly, Crib Nantlle does not part easily for runners. It twists inward, gnarled and stern, reshaping direction and distorting distance.

The grassy slope up Y Garn pitched sharply upward, a wall turning shadow as the last of the twilight drained from the moon-less sky. The night folded over completely. The only clues were occasional flickers of light; others, higher, battling something we couldn’t yet name. Between us and them: grass too wet, mud too soft, feet losing memory of grip. Everywhere sheep eyes catching our beams, glowing back at us like quiet omens, unmoving, unblinking.

It’s hard to explain to non-UK runners why so many trails here feel penned in; shoulder-high stone walls, hemming the runner into narrow passageways. The answer traces back to the 18th and 19th centuries Enclosure Acts. Before, land was often common; grazed collectively, walked freely. As agriculture industrialized and landowners consolidated power, these commons were divided, fenced, and walled, often with no regard for ancient paths or animal movement. Walls became boundaries, property lines, symbols of ownership. The paths that remain are narrow corridors of resistance, squeezed between authority and erosion.

Cymru might feel wild and open, but legal access is largely restricted under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act. The illusion of freedom, is often just that. Much land remains private, and the public’s “right to roam” is carefully circumscribed. This creates a strange duality: Wales offers a deep sense of connection to its land, while access laws often keep that connection at arm’s length. Unlike Scotland, where access is presumed unless harmful, Wales still functions on a model of limited permission, a patchwork of inherited privilege and piecemeal reform.

Unheralded, unsought by the peak-bagging masses; Nantlle ridge, a sawtooth a 9-kilometer arc of high ground offers solitude, drama, and an elemental intimacy. The silhouette strings together six or seven summits, with cliffs that drop abruptly into silence, and views that stretch to the sea. Everything loses its grip here. GPS time doesn’t quite make sense. A single league might consume the better part of half a day. Every so often, you’ll see a faint thread in the grass; desire lines, similar to almost invisible trails (as left by the Elves of Mirkwood). Routes worn by memory. They curve slightly away from signed trail, shaving off gradient or avoiding a waterlogged patch..

Mynydd Drws-y-Coed rises like a blade; narrow, serrated, and unapologetic. Its name, Mountain of the Door of the Trees, speaks to a past landscape long vanished. Only wind, rock, and a door that swings open to those willing to scramble across its exposed spine. At 695 meters, it lacks the altitude of giants, but it commands a reverence that belies its height, and makes you earn the right to continue downwards.

Between its rugged slopes lie the remnants of the Drws-y-Coed copper mines, etched into the mountain’s very bones since at least the 13th century. Miners once delved deep into the earth here, veins bearing only it scars now: collapsed adits, spoil heaps, and remnants of machinery. Like the halls of Moria, it is not the absence of life that haunts, but the echo of what was taken. Not untouched, but touched hard, worked deep, like Khazad-dûm, and left to grow back in its own way. These trails don’t feel ancient, they feel post-industrial.

And yet the mountain holds older secrets still. Near its base, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of Iron Age hut circles, their foundations whispering of lives within this formidable landscape. These dwellings, dating from around 800 BC to AD 400, suggest a community that farmed, herded, and worshipped under the shadow of the ridge. Their presence adds even more depth, a reminder that human connection to this place spans millennia.

The land grew dreamlike. The hour grew shapeless in slow motion: I remember only the hollow sloshing of our footsteps, and a black maw of the mine besides me. Behind three headlamps emerged, ghostlike in their passing. Wedged between, a grim opening, similar to the Dwimorberg’s Paths of the Dead, a perilous haunted route used by Aragorn to summon the Dead Men of Dunharrow. The climbs behind us, the descents ahead, both endless, though neither truly long. Finally, without warning, we tipped over the crown of Moel Hebog. Taking our turns slipping, with brief skids, muttered checks of “I’m fine” like prayer between strangers.

It felt as though we had been swallowed and spit out by the mountain. Forever chewing. The dark began to bleed into blue, there we were, in Beddgelert. We didn’t arrive, we reappeared, As if the race had folded in on itself and dropped us back at our own shadow. Nightfall here isn’t just a dimming. It’s an erasure. Perspective flattens. Your world shrinks to the beam of your headlamp. The second night peels more than something. It hollows you. By dawn, when the first gold cuts through, you feel like you are coming up for air.

There are places where the wind dies and rock rises steep on either side, and you feel unmistakably being watched. Not by people, nor by sheep. By the land itself. Not hostile, nor benevolent. The Welsh have words for this, like “awyrgylch”. The mountain sees you. Not cheering, nor judging. It won’t remember you, it just marks your passing.

The Beddgelert aid station offered a brief exhale as relief turned quickly to haste when volunteers warned us we had about four hours to make the next cut-off. It didn’t add up. The fastest known time for it by a previous runner was also about 4 hours. Without lingering, we pressed on. The trail traced the river at first; a reprieve from vertigo. I couldn’t recall the last time I’d felt a stretch of even ground. A short road lifted our spirits. The tarmac screaming “Araf” in painted white: slow down. We were beyond that now.

We climbed hard toward Cnicht. The effort was laudable, but the climb itself was no longer the antagonist it might have been earlier. We moved well. Route-finding, which had taxed our minds for hours, now felt more fluent. Known as the Welsh Matterhorn for its sharp, triangular profile, Cnicht’s sharp spine and knightly name mark it among the noble heights of Eryri. We arrived at the Nant Gwynant café within 3.5 hours.

They stand like relics. Weathered and wordless. You’ll see more sheep than humans in these hills. Welsh Mountain Sheep, mostly. They outnumber people by laughable margins. They don’t bother with switchbacks or signage. They don’t flinch when you pass. They don’t blink at weather. They’re indifferent to your suffering. They move when they have to, and that’s it. If you make eye contact, you’ll see nothing anthropomorphic. They’ve endured more storms than you’ve trained through. Their ancestors watched these trails form. You’re not impressing them.

We were back on schedule, with Yr Wyddfa twice more: first via the jagged path of Watkin, and after descending half way, a final reckoning via the Miners’ Track. Kevin and I moved without urgency, letting the calm of the day carry us. That quiet dissolved when three runners reappeared and passed us on the descent. My shin screamed with every step down, every footfall slicing like a wire drawn tight. Kevin gave chase without warning. We made a pact to finish together, pulling each other through earlier lows, rallied each other. I was stunned, angry. It took a few minutes to stitch that rupture into something I could carry. By the time I rolled into the checkpoint, the trio was there, Kevin was gone.

I downed a Coke, and in resolve left before the others did. Only thirteen remained in the race, and I wasn’t going to finish last, with a top ten in reach. The last climb teemed with Sunday hikers: sunburnt teenagers in cotton, retirees with poles. I must’ve looked feral, hollow-eyed, salt-crusted, limping through the crowds like a shadow on a mission. From time to time, I dared a glance back. The trio still behind, but fading. By the final switchback, they were dots, if that were them indeed. They had given up the chase. The descent into Llanberis should have felt triumphant. In truth, it was a grim negotiation with pain. I ran stopping only when the stabbing became too sharp to breathe through. I’d nearly caught Kevin but that no longer mattered.

Just like that, it was done. No arch, no timing mat, no buckle, no medal. Just a warm welcome at The Heights. Ana there, Mike too, and volunteers I recognized from earlier. Words fail at the finish of something like this. I recall only a quick bite, half a pint, and a winding bus ride where I passed out instantly, undisturbed by the switchbacks. A missed train connection, ended the day in an hotel in Chester, and hunger that returned with vengeance.

2023: “The Comeback”

I returned to UTS twice more before the story picked up again with real weight. The second time, I was cut short, 50 kilometers in, when my body issued a blunt refusal. My mother was waiting for me then, now waiting somewhere else. Some lessons come in silence, in the space after surrender. The third attempt was quieter still. Mid-pandemic, no race bib, no aid, no crowds. Neither outing carved itself as deeply as that first crossing, nor as sharply as the fourth, which deserves its own telling. That final chapter, years later, wasn’t just a return Eryri, but a return to myself, and to what had become of the race..

Crossing back over the Atlantic took more than shedding time zones. Living in Canada, with a different backdrop, and a different rhythm to my days, returning to Llanberis meant more than boarding a plane, and familiar trains and buses up through North Wales. It meant retracing something older in me. This time I would shared a place with my Canadian friends Adam and Kelsey. They’d flown over to chase their own arcs on this course (Kelsey, in her typically casual brilliance, would go on to place fifth in the 100k).

It wasn’t meant to be the marquee of the year; Swiss Peaks held that title. But I arrived in Llanberis sharp, after long, arduous weeks of mountain training in British Columbian winter, firmed by the steady mind of my coach Nickademus. Unlike that wide-eyed attempt years ago, I didn’t come here to prove I could survive it. I wanted to see how far I’d grown inside the same bones of the course; to hold the present against the shadows of who I’d been.

The race began midday, beneath a sky that felt surprisingly generous; sun-warmed, winds hushed, and clouds holding their breath. I didn’t chase the front this time. That was not my spiel anymore. I watched 50 or so bolt up the road passing Dolbadarn Castle. I stayed quiet in my stride. The opening part up Llanberis path can devour early bravado. I moved with calm intent, passing those whose fire flared too fast, whose breath gave out before the mountain even asked much of them.

At Bwlch Glas, the landscape unfurled like a familiar song. The Pyg Track welcomed me back like an a chorus I knew by heart. I leaned into the descent as if I’d been here just last weekend, not years prior. There’s a peculiar joy in rediscovering a place through muscle memory. My legs remembered before I did. Eryri once as my second home, I now had countless ascents up Yr Wyddfa. This was the mountain of my becoming. Trails once stitched into BMC maps were still stitched into me. While the course had been reversed, rerouted every year, my body still knew which way each arête leaned. Somehow, the place still knew me. I loved it for that.

Long before feet pounded these paths in pursuit of finish lines, before miners quarried the stone, there was wool. Hill farming sustained Eryri for centuries. Sheep were not adornment; they were survival. Their fleece was warmth, wealth, and wholesome. Valleys echoed with the clack of handlooms. You still see the legacy in stone-walled sheepfolds crumbling, in the sagging barns, in the quiet stubbornness of everything that still endures.

Hill farming sustained North Eryri for centuries. Sheep were not just livestock but livelihood, currency, insulation, and identity. Wool meant survival. Entire valleys echoed with the clack of handlooms. You still see the legacy in stone-walled sheepfolds crumbling, in barns roofed in corrugated iron, in the quiet stubbornness of everything that still endures.

At Pen y Pass, the course diverged sharply from the old script, cutting straight up the spine of Glyder Fach, with short switchbacks. My legs felt light, and patient with urgency that isn’t desperation. I passed half a dozen runners without needing to press, and topped out breathing deep and grateful. But the mountain, in its way, reminded me not to mistake flow for invincibility. I caught a toe and launched into a full Superman dive across the rocks. Just a scrape of embarrassment. A little wink from Eryri to keep your head cool. The trail down was scree and slab, the kind of surface I used to tiptoe down. Now part of my favorite terrain, so I opened up, skirting the rim of Cwm Idwal.

You pass Cwm Idwal the way you pass a monument. More than a glacial valley, it a chapter in the Earth’s autobiography. The first place in the UK where someone formally recognized glacial erosion. The likes of Darwin and Kingsley recognized the vast bowl, gouged and sculpted by ancient ice.

Tryfan rose to my left this time, still a mere extra in this showing, its rocky face catching the afternoon light. The weather held up nicely: dry underfoot, still air, sky flung open. My legs, too, seemed to hold back. I passed more runners, another runner from the lowlands, Daan Nieuwenhuis. One of the central players in this narrative, Bjarte Wetteland joined, as we passed Rhiwiau Caws. Not long before the Glen Dena aid station, I passed another protagonist who’d shaped my race’s arc: American legend Sabrina Stanley.

Wales is the land of y ddraig goch, the red dragon. Not just emblazoned on the flag, but also etched into the terrain. This isn’t myth layered on top of geography; it’s myth emerging from it. The land was shaped by volcanic ash, tectonic shifts, glaciers carving out ridges. Dragons are how people once explained a world that cracked and burned and kept shifting underfoot. They don’t perch above the peaks; they are the peaks. The coils of a ridgeline. The sudden snarl of weather. You don’t need to believe in dragons to see one here.

The Carneddau appeared in its glowy glory. A reacquaintance with the ancient spine of upland mass and memory. I no longer held fear or hesitation these summits once summoned. I welcomed them. Pen yr Ole Wen rose steep but familiar, and I climbed it cleanly, cresting as Ian Corless appeared, camera waiting for Sabrina’s approach. She ran smart, steady, and in the end, she’d take second. That’s how. Along the long folds, runners began to sharpen into focus; more bodies turning real and reachable. The sun edged lower, and scrambling while the light still lingered made all the difference.

The final climb had been axed, replaced by a smoother descent from Pen yr Helgi Du into the aid station. I moved with a twinge of loss. The Carneddau, once a proud multi-peaked ridge, had been trimmed down year by year. To date, it has been cut nearly in half, to almost an ordinary other hill, with a few false summits. It’s character, and a lot of the grit, had gone with it. In 2023, I wasn’t in a mood to lament. I kept moving well along the reservoir, into the section that once broke me. It was perhaps the first times I truly lead. We past a couple runners, and dropped another sponsored athlete who’d faded behind. And another two hobbling figures near Capel Curig. Fifty kilometers in, headlamps out, I was exactly where I needed to be: on time, on effort..

The Carneddau appeared in its glowy glory. A reacquaintance with the ancient spine of upland mass and memory. I no longer held fear or hesitation these summits once summoned. I welcomed them. Pen yr Ole Wen rose steep but familiar, and I climbed it cleanly, cresting as Ian Corless appeared, camera waiting for Sabrina’s approach. She ran smart, steady, and in the end, she’d take second. That’s how. Along the long folds, runners began to sharpen into focus; more bodies turning real and reachable. The sun edged lower, and scrambling while the light still lingered made all the difference.

In a land long acquainted with defiance, Eryri is more than mere high ground. At the heart of the Welsh language revival, the land speaks in syllables English once tried to silence. Efforts to restore original Cymru names are part of a broader movement to reclaim identity and heritage. This act of renaming is not merely symbolic; it’s a reclamation of history and a step toward honoring true narratives of the land. The cadence of the Welsh mimics the terrain: soft rises, sudden consonant stops, long vowels like open valleys. As if you’re running through poems.

The course now climbed Moel Siabod, ascending its gentler side. Moel Siabod rises alone, slightly detached from the rest of Eryri’s more famous giants. Because of that, it offers one of the finest panoramic views. From its summit, you can see the horseshoe of Yr Wyddfa, and the Carneddau sprawled to the north. But only when the skies allow it. Tonight it was cloaked in darkness, and in its stillness a keeper of perspective. On the technical Daear Ddu ridge descent, we caught a trio with Anna Carlsson and Alex Homei, threading through the scattered boulders, requiring full attention. With no hesitation I found a rhythm, an amusing, unhinged boulder-hop ballet, and a distraction from the usual playground. Though I suspect many runners were glad to see it end.

From Dolwyddelan up toward Moel Bowydd, the road turned to mire as we crossed the Moelwynion. Into a vague geography that seems but a placeholder of grassy slopes and bogs. No vistas. No clear trail, mere churned grass and flags that offered little more than suggestion. Our headlamps lit the way for others while we saw none ahead. We spent too long scanning and second-guessing, like Frodo and Sam lost in the Dead Marshes. It’s still is on the latest route, and I still don’t understand why. In the murk, Sabrina appeared, while Bjarte eased off. We passed one of the great slate quarries (maybe Bowydd, Votty), but the dark kept most of it hidden. One of the many ghosted wounds on this land, adding a layer of historical intrigue. Blaenau Ffestiniog blinked into view, and we decided, without deciding, to stick together. Some misery is more fun in pairs. I found rhythm on the climbs, Sabrina found strength on the flats, a shared motion, as tide and moon carrying two boats side by side.

Long before carbon poles and carbon-plated padding, there were men who moved through these hills in wooden clogs or hobnail boots. Made for durability. Sometimes dragging slate carts with their backs. You feel the absurdity. Some quarrymen even worked barefoot, looking for more grip on scree, while the quarries were known for their hot and damp conditions.

A climbed over Moelwyn Mawr, the “Great White Hill”, ushered us toward Croesor. Another long, feral ridge of heather, rock, and bog. Not mighty in stature but cunning in form: three false crests, each pretending to be the last, before revealing another. Moelwyn Mawr feels remote even when you’re not alone. Sabrina drifted back to tend her own rhythm; I kept mine feeling oddly serene. The night was clean and kind, the moon overhead a watchful lantern. The descent was its own riddle. I saw the valley I sought, could see the shape of trail far below, but the way down had vanished. A mere flag lay ruined, like a banner after siege, and a high wall to traverse first. Long lost in existential spirals. Eventually, I climbed the wall, found another reflector, and stumbled back on course. Sabrina reappeared, also confused, but calm.

Cnicht rose next, just as the sky began to bloom with dawn. Sabrina and I drifted apart again, each taking our own tempo. On the ridge the course slipped out from under me, again. This time in daylight. I’d veered just below the proper trail, following another rogue flag, a different trail, out of sync with the one above. When I realized, several minutes in, I stopped to weigh my options: up and over the crest to investigate, or backtrack to known ground? I chose the latter, paying the cost of losing another 15 minutes. I should’ve crested. Again, Sabrina rejoined me, and we continued leaping bogs and puddles. More than once, we sank waist-deep into the sodden earth. Luckily, no “dead things, dead faces in the water” here.

Gwastadannas Farm came as the sun began to press down in earnest, settling heavy on our shoulders. Nestled in the upper reaches of Nant Gwynant, a symbolic waypoint, where toil meets terrain, and the stewardship of land brushed up against modern pilgrimage of endurance. Tracing the flanks of Yr Wyddfa, beneath tree-filtered light, the ground had been pummeled by previous runners. Samwise would’ve pointed out: “Good tilled land, Mr. Frodo. That’s what keeps the world going.” I’d surged ahead at first, made a short detour, while Sabrina found another gear. Steadily, relentless, I labored behind. It wasn’t until we reached the sounds of the Afon Glaslyn river, marching through the valley, that I began to feel good again.

Leaving Beddgelert, the infamous Nantlle loomed like a jagged memory I’d come to rewrite. Last time, it had taken something. This time, I wanted to meet it on my terms. I warned Sabrina what to expect; each deceptive peak promising to be the last. Knowing helped, I think. She took it in stride, and we kept a firm rhythm. Tired, of course, but intact. The things expectations do to you. Sabrina commented it was the hardest thing she’d done; harder than the Hardrock course record, or the Nolan’s 14 FKT. At Rhydd Ddu, we finally found others who had not fared so well. Hollow-eyed, one blinking into the void, one ready to quit. I told them the worst had passed. Whether they believed me didn’t matter.

Turns out, I was more hollow than I let on. The climb up Yr Wyddfa from this side is long but rarely intimidating. Except when it’s 34 degrees Celsius, while the air doesn’t move here. Sabrina launched surged upward like Éowyn unflinching on the battlefield. I followed, slower, watching her grow smaller. The last of the 25k runners were descending. I had to sit for a moment, out of water already, and there was still a thousand feet left to go.

Then came the surge: a flood of 50k runners ascending the Watkin Path, stringing up the trail in a slow, panting line. Solitude gave way to chaos, congestion. It didn’t lift me, but it kept my mind from sinking. I moved into passing mode. Threading between bodies, stepping off trail when needed, whispering “On your left. Careful here. Thank you.” It was slow work, dodging along technical rock, waiting to squeeze through gaps. Sketchy. We’d already run 140 kilometers. This wasn’t the time to scramble for space. A casualty of a bloated course. At the summit, the shelter was closed. I had hoped for something, anything. Down the Ranger Path I turned with dry flasks and a growing urgency. I stuck to the course while others snuck along the easier train tracks. I flowed downhill with cautious speed, pausing only to gulp from a shallow stream.

At the massive aid station below, lines snaked out, dozens queued to refill. I waited too, for a few minutes. Then decided to cut in. I was still racing for a top ten. People nodded understanding. The shift was clear, after 15 hours of VIP treatment, I had gone invisible. The climb up Mynydd Mawr was short, steep, and brutal on weary legs. I bore no staff, my poles had long since splintered. Still, I moved better than most, some startled by my bib. It’s a strange dissonance: to be so deep into something, only to be surrounded by fresh legs and fresh complaints. No disrespect to anyone, it’s just a jarring collision of different stories.

Leaving the final aid station in Betws Garmon, I wolfed down a lembas-like sandwich while chatting with another runner. As I jogged off, he stared like I’d grown a second head. “We’re still running?” “Aye,” I replied. “Apparently.” Moel Elio, easy on a normal day, with its three humps. I could see the sigh ripple through each runner behind me at the sight of next hill. A cramped-up elderly man cried as he tried to climb the laddered fence, but moved aside as I approached. The descent into Llanberis should’ve felt like celebration. It hardly did. But I ran it all the same.

No one looked up when I finished. Two 50k runners had their moment, cheered, photographed, congratulated, while I slid past without a ripple. With my hands before my eyes, I passed the line quietly. That quiet suited me. I’d finished fifteen hours faster than my first time around. The gaps were mine to measure: between then and now, between start and finish, between what the land demanded and what I had to give. I knew where I’d been. The companions found and lost again. I didn’t need a finish line to mark the passage. Eryri had done that.

2025: Of What Was, and Is No More

Races don’t lose their character all at once. The shift happens incrementally—through edits framed as improvements, efficiencies justified by scale, narratives rewritten for broader appeal. And then one year, you come back, and it’s not the same race. Not quite. So what now? Do we mourn the old course? Accept the inevitable? Resist the change? No, not necessarily. But we must ask what kind of culture we are cultivating. What do we preserve? Do we make space for wonder, do we need to smooth out the bumps for easier consumption? I know some things won’t be the same again. The old course won’t return. That’s fine. The question isn’t how to stop change, but to see the change, to understand it. If races evolve, then so must we, careful not to lose the story in the telling.

My return to Eryri in 2023 was a personal test, but also a study in what happens when an event forged in grit gets is absorbed into a more polished machinery; a study of how small changes, each defensible on their own, can shift the spirit of an event. When I first ran here, the course was erratic, flawed at times, yes, but in the best way. Brutal cut-offs, vague flagging, and questionable aid. But with soul. In that roughness, authenticity lived, and intimacy was shared; connected with others in moments of doubt. Shared silence with spectacle. No race is immune to the machinery of scale. What’s concerning is when the push for growth reshapes everything in its path. The old spirit, once unbranded and unruly, now gently curated. What was once a priceless adventure can quickly become a cheap product.

Since its inception, UTS changed. Not just in direction, distance, or elevation, but in character. In temperament. In tone. It lost it’s raw toughness each year. Some parts dropped. Some of the most character-defining climbs replaced by, if still rugged, alternatives. The wildness hasn’t disappeared, but it’s been trimmed; less a test of adaptability, more an optimized experience. What it asks of the runner, and what it offers in return, feels unmistakably different.

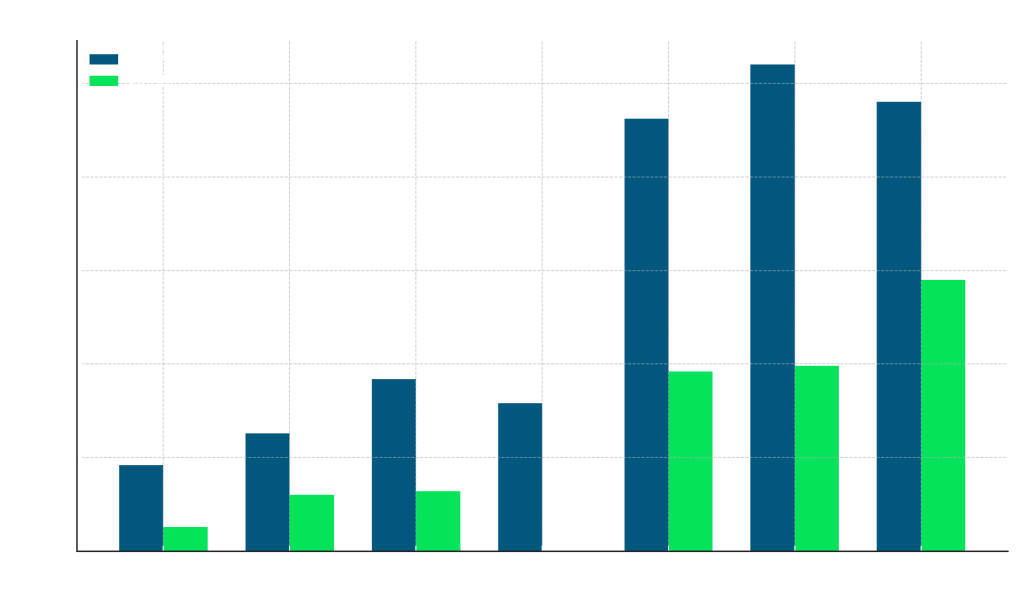

This all isn’t just anecdotal. The numbers tell their own story. Over the years, the 100-mile course quietly lost ground, in terrain and spirit. Elevation dipped from nearly 12,000 metres to under 9,700. Distance shortened. Finishing rates rose. In 2018, only 46 runners started the 100-miler, and just 28% made it to the end. By 2025, nearly 500 runners lined up, with over 60% reaching the finish. That’s not a fluke. It’s a shift in design logic. When more and more finish, fewer and fewer are tested at the edge of what they believed was possible. Participation across all distances ballooned from just over 200 in 2018 to nearly 3,000 in 2025. That kind of growth doesn’t just happen. The intimacy of early editions weren’t a product of nostalgia. They were a product of scale, and of design choices that favored friction over flow.

The 2025 course is again a bit faster, shorter, cleaner in places. Less time between aid stations. In the name of efficiency, or scalability, we’ve lost not just rawness or vertical meters, but friction, and with it, texture. The friction of a long mountain range. The friction of solitude and desolation. Friction is what makes memory cling. The experience of what it was. When we lose friction, we lose memory, the ability to carry place with us, and the chance for a race to become meaningful, not just a challenge.

Still, “easier” here is relative: no climb that doesn’t demand something extra. The bogs still take your legs. What’s runnable is often exposed, or wet, slow. What’s sheltered is short. Nantlle still humbles. With improved markings, and maturing infrastructure, you still carry the GPX file like a rosary, highlighting the terrain’s refusal to conform to race logic. Many runners still go off course. Some find their way back. Some don’t.

It still stings, but the magical spell is gone. What’s striking in the data is not some dramatic plunge; it’s the subtle, quiet sanding down. Elevation dropped slightly over time. Average finish times trended downward. Completion rates crept up. Each year’s course tweaks, minor shifts in elevation, seem modest on their own. A few kilometers here, an aid station shuffle there. Even the finishing rates, though fluctuating, don’t scream revolution. Taken together, they point to a reshaping of the experience. It rarely happens all at once. Transformation is often gradual, year by year sometimes easy to miss. We often fail to notice what slips through the cracks, when the race alters its rhythm.

The 25k, 50k, 100k, and 160k races now crowd the paths at peak hours. Ridges become bottlenecks. Solitude gives way to congestion. Aid stations become choke points, airport terminals, with bland provisions. Volunteers are overrun. More people, means more pressure, more precision, and less room for serendipity. That’s not just a logistical hiccup; it is the new emotional register of the race. What’s lost isn’t just efficiency; it’s depth. The affective fabric of the race, that intimacy is hard to find now: rationed, diluted.

The risk is not that all races will become easy. It’s that they’ll become indistinct; interchangeable in format, flattened in memory, reduced to a digital badge or shareable clip. Participation now orbits a more scripted, consumable spectacle. It replicates the aesthetics of difficulty while smoothing out contradictions. Less relational, more procedural. Institutionalized. The edges filed down. With each edit, closer to standardization. Not just a shift in terrain. A shift in power: from runner to race organizer, from shared narrative to pre-packaged story.

The UTMBfication of UTS is not a villain in a single act; it’s a thousand edits that eventually shift the plot. The course didn’t get easier all at once. But by degrees. Experience by experience, the story changes. So the critique isn’t that UTMB ruined the race. That would be too easy, and not quite honest. It’s that the spirit of it, something hard to define, gets lost when experience is optimized for consumption. When a race becomes a brand extension. When adventure is bent into deliverables. I don’t believe everything has to be marketable to be meaningful. Not every trail needs to be streamlined. When we equate growth with simplification, we risk erasing the very qualities that made us fall in love in the first place. That aches, not because I don’t want change, but because I want change with depth. It’s not anti-change to ask whether we’re building something richer, or just more scalable. Change that knows what it’s leaving behind. We owe ourselves a fuller kind of progress, one that doesn’t pave over what is rare and real.

Many sign up “because it gives a stone” and it’s logistically easy from where they live. I’ve heard it over and over. That calculus, of “convenience plus UTMB currency”, risks reducing a once-rich event to a checkbox. A stepping stone in a gamified progression system. When that becomes the dominant logic, the field begins to shift. The start line fills not with people drawn to Eryri’s history, its terrain, its sense of place, but with runners chasing their next eligibility token. UTS becomes a proxy: not a destination, but a means to something else. What once demanded presence and patience now becomes a transaction. You come, you complete, you collect. In that framework, the race’s particularity—its wildness, weather, linguistic and cultural layers—becomes background noise. And the experience becomes flatter, not just for the individual, but for the collective. What disappears isn’t just depth. It’s intentionality.

Beyond points, UTMB’s architecture extends to its sprawling World Series, a franchised circuit that licenses races worldwide under strict commercial terms (Since 2021, UTMB has been part-owned by the Ironman Group, itself controlled by Advance Publications, a global media conglomerate better known for Condé Nast titles like Vogue and Wired). Events pay substantial fees for affiliation, adopt standardized media and timing systems, and surrender narrative control in exchange for brand association. The scale is staggering: UTMB now operates 51 races across 28 countries, many imported via acquisition or conversion of legacy events . The result is a global homogenization of trail racing: branded aid stations, sponsor visibility, and curated experiences that align with global event management. It’s no longer enough to host a challenging race; you’ve got to fit the template. That is institutional transformation, not incidental branding; and it’s the mechanism by which a once-local race like UTS can tip from radical to sanitized, unless it consciously resists.

Runners arrive with different expectations. They spend less time in the region, less energy engaging with its communities, and often leave without much sense of where they actually were. Local economies may see a spike in bookings, but not in connection. The land bears the burden: trails wear down under surges of participants whose primary goal is to finish, not to understand or protect the terrain. When a race becomes a means to an end, its setting becomes incidental, and places like Eryri, already vulnerable to overuse and extractive tourism, are treated less as living landscapes and more as branded backdrops. The cost is ecological. It’s relational. And it compounds year by year.

This is not an isolated story; it’s a mirror of a broader pattern, where even the most rugged experiences are being optimized for consumption. Reformatted to fit into scalable, digestible formats. Not just the race, but landscapes, cultures, relationships. The language shifts from discovery to delivery, from presence to product. You don’t need to be cynical to notice it. That’s the cost of UTMBfication; not just commercialization, but compression, flattening of weirdness, erasure of uncertainty, dilution of intimacy. Yet, knowing that, I still want there to be room. For newcomers. For transformation. For the sport to grow. But also room for the ineffable, the grit, the unplanned. That’s what motivates me and many others. Where stories come to life.

This isn’t just a running story either. It’s Airbnb gutting mountain towns for tourist efficiency. It’s Spotify smoothing the chaos out of music discovery. In the productivity framing of meditation apps. In how even friendships now perform for digital affirmation. It’s the optimization of everything. The promise of more access, reach, reliability; at the cost of unpredictability, weirdness, and soul. The logic is the same: make it repeatable, make it legible, make it scale. But scale strips stories of their knots and inconsistencies. It trades lived ambiguity for marketable clarity. When that logic reaches places like Eryri, where mist and disorientation have always been part of the truth, we don’t just lose access to challenge. We lose access to wonder.

UTS is still one of the hardest 100 milers. But let’s not pretend this is a surprise. The trade-off is clear. UTMB’s brings visibility, predictability, marketability, and crowds; the currency of the algorithm. A race’s identity compressed into a shareable package. Unique moments are no longer central, they’re residual. The 100-mile distance becomes a subplot. As I’ve written before: growth without meaningful intention is just deliberate expansion. And experience scaled is experience diluted.

Trail running in the UK is rooted in centuries-old footpaths and agricultural memory. Fell running, especially, carries a unique, cultural ethic of self-reliance, navigation, and unadorned difficulty. There are no medals for finishers, no fanfare; just the land, and your relationship to it. Originally, UTS honored this heritage. It borrowed from fell culture: the rough terrain, the minimal markings, the sense that part of the race was about reading the land as much as moving through it. It asked runners not just to complete a course, but to know it. In moving toward global trail (UTMB) norms UTS risks trading that lineage for legibility.

Growth without friction is like those spruce plantations above Betws Garmon, planted for ease and efficiency. They rise in straight lines, they offer passage without resistance. Shallow-rooted and brittle beneath. No underbrush, no birdsong, no wild. Just uniformity. Shielded from wind, never learned to root itself against strain Never meant to weather storms, only to be harvested. That’s what some races are starting to feel like. Streamlined, fast, forgettable. But the friction, the hard climbs, the missed turns, the moments that don’t go to plan, that’s what thickens the bark. That’s what roots you in the memory of a place. Without it, you’re just passing through, untouched by it.

Friction is what gives growth its shape. Friction is the tension that refines, the resistance that reveals limits and strength. It’s the difficult conversation that forces clarity, the failure that redirects effort, the steep climb that builds endurance. It’s the grit in the system that demands adaptation. Growth without friction might be possible. But it is often growth without anchoring, without meaning, without memory. It expands, but doesn’t deepen. It accumulates, but doesn’t transform. It moves fast, but doesn’t know where it’s going. Would you call that growth?

Friction, then, isn’t just difficulty; it’s engagement. It’s anything that disrupts passive consumption and insists on presence: emotional uncertainty, institutional complexity, terrain that won’t be choreographed. It resists clean lines and easy metrics. Weather that doesn’t obey forecasts. Courses that demand judgment, not just fitness. That resistance is what gives a race its soul. Not because it punishes, but because it asks something real. Without it, the experience becomes just another delivery system, smooth and forgettable. Friction isn’t ambiance. It’s a design choice. If we want trail running to carry meaning, not just momentum, we have to protect it as such.

In the case of UTS, many sign up “because it gives a stone” and it’s logistically easy from where they live. That calculus—of “convenience plus UTMB currency”—risks reducing a once-rich event to a checkbox. What’s worse: it means fields are filled not with people drawn to Eryri’s story or its mystery, but with those chasing their next ticket in the global lottery.

Let me be clear: I welcome new runners. I love seeing someone discover what long days in wild places can do to you. There is a place, and a need, for shorter races, and first attempts. Access matters. Deeply. I celebrate it. I want more people to feel welcome. I also believe we need to hold onto the kinds of experiences that resist packaging. The ones that aren’t algorithm-friendly, that don’t scale well, that ask more of us than just finishing. This is not a call to retreat into exclusivity or nostalgia. Inclusion and challenge are not opposites. Inclusion doesn’t require dilution.

Access is not the same as equity, and visibility doesn’t guarantee depth. The risk isn’t growth itself; it’s what gets sacrificed in its name, and who gets to decide. We shouldn’t be asking whether change is good or bad, but whether it’s intentional, whether it listens, whether it serves more than just the metrics. Real evolution doesn’t mean scaling up what worked, it means returning, again, to what matters, and being willing to let go of what doesn’t.

There’s a temptation to treat authenticity and efficiency as opposites. As if meaning only lives in chaos, and every refinement flattens the experience. That binary doesn’t hold. Better markings, safer descents, predictable logistics, these aren’t just conveniences, they can be acts of inclusion. For newer runners, for those less familiar with fell culture or mountain navigation, those changes can be the difference between participation and exclusion. Refinement, done with care, doesn’t have to mean erasure. The real question isn’t whether a course is marked or not; it’s what those markings are in service of? We need to ask not just what’s gained or lost, but for whom, and whether our ideas around difficulty, value, and legitimacy are expansive enough to include the people we claim to welcome.

This isn’t gatekeeping; it’s caretaking. I want the door flung open, but I don’t want the house gutted and remodeled to look like everything else. Inclusion isn’t about sanding edges; it’s about recognizing that sharp edges shape us. We can preserve challenge, uncertainty, character, without making them barriers to entry. It means trusting that people are capable of rising to difficulty. Just like Mike trusted me. It’s not elitist to want some courses to remain difficult, confusing, unpredictable. It’s honest. Experiences that resist commodification are worth preserving, precisely because they challenge and transform.

If what you want is a smoother, safer, better-marked race, you’re not starved for choice. There are thousands of shorter, friendlier events: trail half-marathons, 10Ks, looped ultras with rolling terrain and polished logistics. In North America alone, nearly 3,000 ultras were held last year, most of them runnable, well-aided, and far less demanding than UTS. Add in Europe, Asia, Australia, and you’re looking at tens of thousands of options. Even in the UK, hundreds of fell and trail races run every year, many of them beginner-friendly and well-signed. We don’t need every race to be hard. We certainly don’t need to make the hard ones easier.

I started by writing out how I once was a wide-eyed newcomer. Chasing a finish, a foothold. I know what it means to want in. The joy of your first summit, your first long day in the mountains. And well-supported events, shorter courses, clean markings, they can be powerful gateways, not shortcuts. What I’m asking isn’t that everyone cut their teeth in chaos. It’s that we hold space for races that still ask something different. This isn’t about purism. It’s about pluralism. There should be room for a range of experiences; for the runnable and the ruinous, the polished and the raw. I’m not critiquing the joy; I’m critiquing the machinery that quietly narrows what that joy is allowed to look like. If we don’t make space for difference, we lose more than difficulty. As I tried to describe, we lose the possibility of transformation.

You can train for the climbing. You can dial your nutrition. You can waterproof everything you carry. But to run well in Eryri, still, you need something harder to program. You need to feel the place. Let it shape you as much as you try to move through it. Not just endure it. That’s where the race becomes something else. It’s not the challenge itself, it’s the dialogue.

Every year I felt a hunger to return. That ended in 2023. UTS isn’t gone. It is caught between being a present and being a product. The question isn’t just whether it’s still hard, it is, for me too. But does it still belong to those who were drawn to it in the first place, those who made its inception happen? Or has it slipped into a catalog of elsewhere, a qualifier, a point to collect “running stones” for UTMB, another item on a finisher’s list. We all know the answer.

We need to protect space for these kinds of experiences. In a culture increasingly obsessed with predictability, metrics, and mastery, we need spaces that resist being measured. That don’t resolve cleanly. Spaces where the trail goes quiet, where things go wrong, where connection happens through shared vulnerability. These are not inefficiencies, they are part of what makes running transformative rather than transactional. Not everyone needs to be pushed to their edge, but everyone deserves the chance to find it. That kind of encounter doesn’t scale, and it shouldn’t have to. Some things are worth preserving because they’re difficult to replicate.

If we want something more than elegy, we have to try. What would it mean to design a race that resists extraction, not just in its rhetoric but in its structure? Maybe it looks like community-led governance, where locals, runners, and Welsh cultural organizations shape the course and cap the scale. Maybe it starts with local-first registration. Maybe it means limiting field sizes. What matters is intent: to hold friction and wonder not as nostalgic leftovers, but as design principles. To imagine trail running not as a product to scale, but a relationship to deepen. We don’t need a blueprint yet. But we need to ask better questions about what we’re building, and who it’s really for.

Making space means designing with values other than scalability. It could mean preserving sections that are disorienting, even if they’re harder to organize. It could mean rethinking how we structure aid. It could mean protecting time cut-offs that ask something more, or limiting field sizes to preserve solitude. More than that, it’s a mindset: to plan a race not as a product, but as an encounter. To treat unpredictability not as a bug, but as a feature. To prioritize awyrgylch over optics. To leave room for the kind of magic that stays with someone for years.

As runners, we have a role in this. We shape the culture with what we praise, share, demand. If we only celebrate polished experiences, visibility, we train the system to deliver more of the same. We can choose differently: honor the detours, collapses, the quiet victories no one else saw. We can stop expecting every course to fit neatly into a training plan, or a social feed. We can remember that some of the most meaningful runs are the ones we can’t explain. If we want events that hold onto soul, we have to be runners who look for it, and protect it when we find it.

This means asking more of ourselves than just finishing. It means showing up attentive: to the land, volunteers, the stories that came before. It means letting go of the idea that a race owes us anything beyond the chance to be changed by it. If we treat races like transactions—sign up, execute, collect running stones—we’ll end up with courses that reflect that emptiness. But if we move through these places with curiosity, humility, presence, we become part of something richer. The soul of a race isn’t something organizers can manufacture or algorithms can optimize. It’s what we carry in, and what we choose to leave behind.

The good news is: we’re not too late. The trail doesn’t forget. The mountain doesn’t care about market logic. Somewhere in every race, there’s a chance for real encounter; that leaves you scraped, bewildered, alive. That won’t go away entirely, not as long as we remember what brought us here: not convenience, but meaning. We may not be able to undo all changes, but we can choose which ones we carry forward. We can be architects of depth, not just passengers of scale.

So ask more of the events you love, or want to love. Ask more of yourself as you move through them. Support races that put soul above spectacle. Remember the stories that don’t trend. If we want a running culture with depth, we have to be willing to defend its complexity. Protect the weird, the slow, the uncertain. Because when we lose the wildness, not just of place, but of experience, we lose something elemental, something that no finish line can replace. The future of trail running doesn’t need to look like its past. But it does need to feel like something worth returning to.

Hireath

We don’t write critiques like this because we want things to stay the same. We write them because something once felt real enough to hold onto. What we defend isn’t nostalgia; it’s texture, friction. A meaning that emerges only when difficulty, place, and presence align. Not perfectly, but memorably. When that begins to fray, when scale outpaces soul, we have to ask what, if anything, should remain intact. Not out of stubbornness, but out of responsibility. To memory. To the land. To the stories we build our lives around. That’s why I came back to Eryri. Not to reclaim what was lost, but to sit with the part of me that still reaches for it.

There’s a word for that kind of reaching. We need language for what we’re losing. For that, the Welsh gave us: “hiraeth.” There’s no clean translation. Not quite longing or homesickness. It’s the grief for a place that may never have fully existed, but still lives somewhere in you. A home, a place you remember without memory. A place you carry in your bones, even if you can’t name it. In Eryri, hiraeth is thick and omnipresent. You don’t need to be Welsh to feel it. You just need to be tired enough, or quiet enough, feeling enough, awake enough, to notice what you miss, and not know why. I returned to Eryri because of hiraeth.

While, it’s ‘easy’ to mourn what’s gone. It’s harder to accept that what we miss may never have fully been. That’s what hiraeth has thought me: that belonging isn’t always rooted in what’s preserved, it can be found in what eludes us; what you chase not to catch, but to remember who you were when you first went after it. Hiraeth matters; not just as a feeling, but as a form of resistance. A way to name the ache before it disappears completely.

After finishing in 2023, I stumbled a long way back to the empty home I was staying. Cold, no energy to put on a jacket. I took one sip of the finish line beer, then let it sit untouched. Hungry but no appetite. Cramped up. Quiet. My phone dead. There was no one to celebrate with. In that strange, liminal stillness, I felt something raw and unfiltered that no race-day highlight reel could ever capture. The aftershock of effort settling into the bones. The solitude wasn’t sad, exactly. It was honest. The kind of emptiness that doesn’t demand to be filled.

That kind of ending doesn’t trend. It doesn’t slot easily into a race report or Instagram post. But it was real. It mattered. I didn’t need spectacle. I needed stillness. Not validation, but a quiet place to process what had happened. That’s what some of us are trying to hold on to. Not the myth of suffering, but the depth of experience. Maybe that evening, I understood what hiraeth really is: not wanting to go back, but wanting to belong to something that no longer quite belongs to you. And loving it anyway.

That’s what I want to protect. Not just steep climbs or technical descents, but the conditions that allow for this encounter; with place, effort, self. Experiences that don’t need to be witnessed to be meaningful. That don’t compress into content. When the noise fades, the crowd moves on, what remains should be more than a medal or a time. It should be a trace. Something that lingers. Not to be shared, but carried.

I don’t expect everyone to feel this way about UTS. But I’d be surprised if most runners didn’t carry their own version of hiraeth. You hear it in the way others speak about the race they can’t stop thinking about. I think most runners, if they look back far enough, have their own version. A course that shaped them. A finish line that mattered not for the time it took to reach it, but for what it asked along the way. You might not call it hiraeth. You might not have words for it at all. Chances are, you’ve felt it. We owe those places, and those versions of ourselves, not just memory, but protection. Not just elegy, but care.

Perhaps that’s the irony of the return: you don’t find what you came looking for. You find the shape of what’s changed; the texture of what’s missing. If you’re lucky, you also find what still holds. I returned to step inside of it. To feel how the absence echoed against my own change. That’s hiraeth: a resonance. I’ll carry it with me, just like I carry Eryri and UTS. Not for what it was, but for what it gave. Hiraeth doesn’t ask you to go back. It asks you to understand you might not be able to, and to love the place anyway. Races change. So do we. Some experiences are meant to be remembered. Ultra Trail Snowdonia is my hiraeth.

I don’t know if I’ll return to UTS again. Maybe. Maybe not. I do know I’ll keep returning to what it gave me: a deeper way of being, a way to listen to place, history, effort. That’s what I want to carry forward. That’s what I want to protect. With discernment. With care. Maybe that’s what growth actually looks like; not chasing more, but learning what’s worth staying close to.