by Jonathan van Geuns, June 1, 2025

There’s something strange and almost sacred about your first big ultra. Your first 50 miler. Your first 100. Maybe even your first 200. Embarking on your first big one is not just a physical challenge; it’s a psychological journey that taps into various mental faculties. Interestingly, the very inexperience that might seem like a disadvantage can, in fact, serve as a powerful asset. Understanding these psychological components underscores the importance of mindset in ultrarunning. For newcomers, embracing the unknown and maintaining a positive, open-minded approach can be as critical as physical preparation.

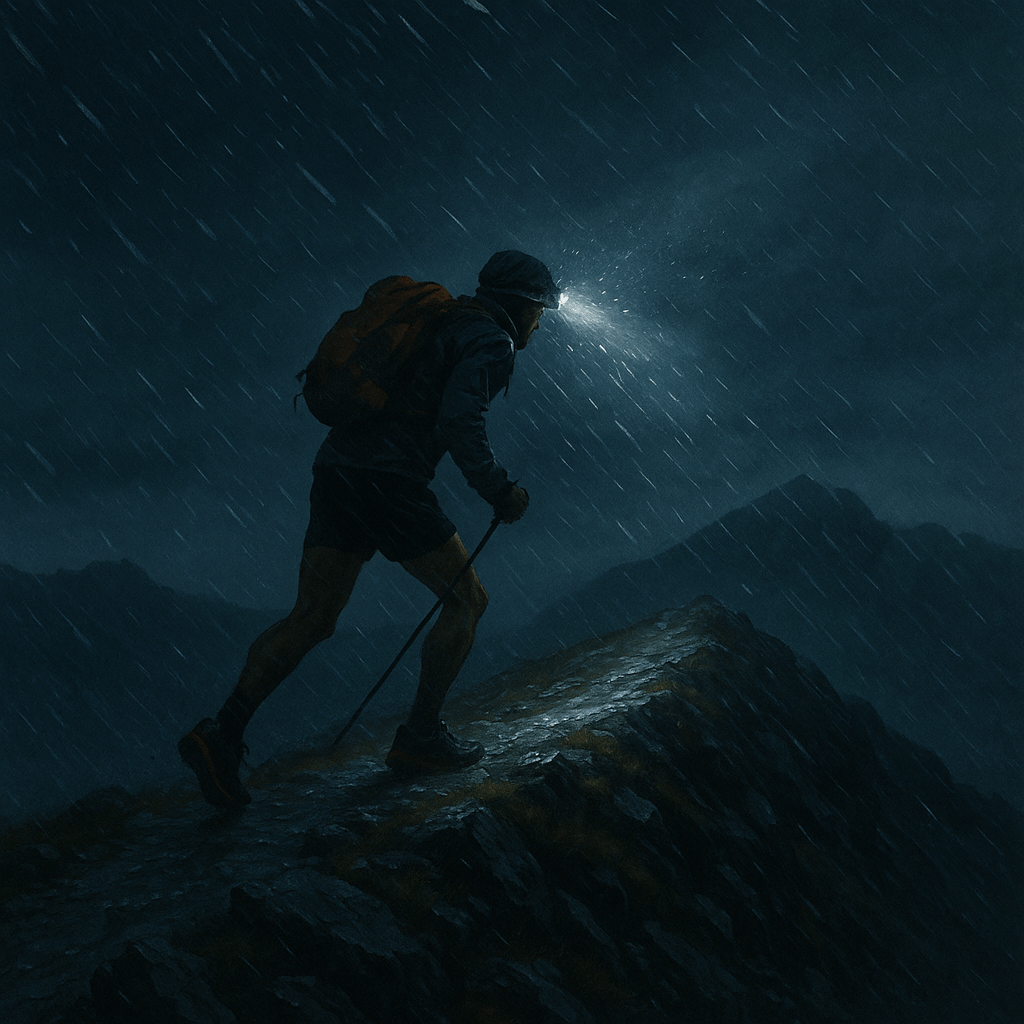

Snowdonia, 2018

My first big one was a Welsh ogre: Snowdonia 100 (UTS). A race that felt more like a pilgrimage than any organized event. It was +170 kilometers through bare, rugged terrain; off-trail, unrelenting, spiked with over 12,000 meters(!) or ~40.000 feet of elevation gain. The landscape stark, wet, and wild, in a way that doesn’t care how much experience you have.

The first night, the sky opened into freezing, sharp, wind-whipped sleet that pelted the entire ridgeline like it wanted to shrug us off (and it did, for ~50% of us). We stretched over slated ridges under slanted moonlight, scrambling over wet and sketchy terrain. I was 35 miles in when my right shin flared with pain; an inflammation so severe that running on flats or descents became quite impossible.

Strangely, quitting never crossed my mind. The pain just became part of the journey. This was the journey. I didn’t know then what I would know later. I didn’t know how easy it would be in future races to mentally calculate the exit signs. I was too new to fear it properly. There was only forward. In that bluntness, that naivety, I found presence, something close to freedom. I moved forward because movement was all there was.

It took me 46(!) hours to finish. I came in 10th. These numbers don’t matter. What matters is that I never once considered stopping. If I ran that same race today, I am not sure how I would fare. Smarter, for sure. More cautious. I’d weigh the risks. I hadn’t built the mental file of failure modes and internalized all the calculations. So I sometimes wonder whether I’d have the same clarity, the same drive, presence, purity of effort. Back then, I wasn’t running against anything; not against failure, time, expectations. I was just running, and stumbling.

Naïveté as fuel

Experience is an asset, but it also brings knowledge of how things can go wrong. It brings caution, strategy, perhaps fear. None of those are bad. They’re part of what makes sustained performance possible. They also make the first time something special. When you don’t know what you’re doing, you might go farther than you thought possible. Not in spite of your inexperience, but because of it.

The first time you toe the line of something that feels impossible, you don’t carry a tidy folder of past failures. You carry questions. In those questions lies possibility. In that “beginner’s mindset” or “cognitive openness,” your brain is more receptive to novel experiences, less bound by patterns or expectations. As opposed to overanalyzing or anticipating every challenge that can lead to mental fatigue. You’re not managing your threshold. You’re defining it.

There’s some research to back this up.1 Studies in endurance sports show that perceived exertion is influenced not just by physical strain, but by anticipation, expectation, and mental framing. When runners are unaware of the exact duration or intensity of what’s ahead, they often report lower perceived exertion levels.2 When you’re new, you might not have enough context to fear the second half of a race. So when it hits, it just hits, and you deal with it. There’s clarity in not over-preparing for the pain.

Research indicates that successful ultrarunners often exhibit high levels of mental toughness and self-efficacy; the ability to persevere through challenges and the belief in one’s capabilities to achieve a goal.3 These traits are crucial for enduring the unpredictable and grueling nature of ultras. Interestingly, first-timers may naturally tap into these qualities, driven by the sheer determination to complete the unknown.

I’m not arguing that ignorance is better than knowledge. Anyone who’s run multiple ultra’s knows how valuable that hard-earned wisdom becomes. But your first big one is often not about grace. It’s often about grit, surprise, and sometimes sheer accident. That makes it honest and raw. There’s no polished identity to protect, no PR to beat, no sense of mastery to maintain. You’re just a human animal trying to survive.

Furthermore, what no one tells you about your first big ultra is how it stays with you. Not just in your legs, but in the architecture of your memory. After the blisters fade and your sleep returns to normal, something remains. A kind of awe at what your body and mind just did, together, without a script.

In the days that followed UTS, I felt triumphant, yet hollowed out. Like something unnecessary had been burned off. Something had happened out there that changed the texture of how I saw difficulty, distance, and myself. That first finish isn’t just a physical milestone. It’s a psychological rupture. Something inside you doesn’t quite come back the same. That’s part of the gift: not just the not-knowing, but the never-un-knowing.

The gift of not knowing

Sometimes what pushes you forward isn’t belief in yourself, but just not knowing any better. That’s not a weakness, that’s a gift. There’s magic in not yet knowing what’s coming. In not understanding exactly how far the distance stretches, or how deep the fatigue can go. When you don’t know how bad it can get, you also don’t know where your limits are. You haven’t rehearsed your collapse. You haven’t pre-written your failure. You’re not carrying all the ghosts of races past. You’re just here. That’s a gift. A gift that perhaps only exists once.

The first time you run this far (whatever this far means for you) you are pure potential. You haven’t yet built the mental map that says “this is where it gets hard” or “this is where I usually fall apart.” So instead, you respond to the moment. Maybe with awe. Maybe with stubbornness. Maybe with tears. But you respond. In that rawness, there is power

If you’re new to the sport, don’t rush to trade that in. Don’t assume that with less knowledge you have less strength. So when it gets hard, don’t think, I don’t belong here. Think: Of course it’s hard. I’m doing something I’ve never done before. When you feel lost, don’t assume you’re failing. You’re just mapping new territory. You are, quite literally, going where you’ve never gone. There is no greater privilege than that. Let yourself be surprised, be moved.

Let It be what It was

Prepare as best you can, but accept that most of the race will be improvised. Practice being curious, not just strong. Practice showing up when it’s no longer fun. Practice staying in the moment rather than calculating how much is left. Don’t be afraid to be a little naive. That edge, that openness, might just carry you farther than any training block ever could. The first one isn’t about proving anything. It’s about discovering who you are when the usual stories about yourself fall apart. Let it teach you. Let it undo you a little. That’s part of growing.

You’ll only get this once. You only get one first time. One chance to not know, and to go anyway. While you’ll learn to race smarter, fuel better, train more efficient, recover faster, part of you will always carry that early version of yourself; the one who didn’t yet know where and how long the edge was, and went looking for it anyway.

You don’t need to try to recreate that experience. In fact, you can’t. Later races will ask different things of you. What you can do is carry forward the spirit of that first time: the openness, willingness to be surprised, strange clarity that comes from not needing to have it all figured out. So if you’re standing at the start line of your first big one—scared, unsure, maybe wildly underprepared, know this: you’re exactly where you need to be. You don’t have to feel ready. You just have to begin. Trust that not knowing is its own kind of strength.

- Hutchinson, J. C. (2021). Perceived effort and exertion. In Z. Zenko & L. Jones (Eds.), Essentials of exercise and sport psychology: An open access textbook (pp. 294–315). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology..

↩︎ - van Sprundel, M.. Running Smart: How Science Can Improve Your Endurance and Performance. Translated by Guinan, D.. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2021.

↩︎ - Thorntona O.R., et al. The Psychological Indicators of Success in Ultrarunning-A Review of the Current Psychological Predictors in Ultrarunning. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2023;7:730-736.

↩︎