PART 1

by Jonathan van Geuns, May 22, 2025 (updated May 24, 2025; updated May 30, 2025)

May 20, 2025, 11 AM (EST)

I didn’t just clear my calendar. I built this season around this day: the opening of Cocodona 250 registration. The race I missed this year because of an injury. I had shifted my mind from the grief of missing out to the joy of returning. The race that had become, slowly, the last half decade, the gravitational center of my running life.

And then it was gone. Not the race, but my access to it, swallowed by a “register” button that wouldn’t click, a server that wouldn’t load, a system that couldn’t handle what it advertised. Frozen screens and growing desperation. For 15 minutes I sat there, in a hotel lobby, clicking and refreshing, again, and again.

The UltraSignup site stalled and glitched its way to a flaming red “sold-out” banner. The website couldn’t handle the traffic. It crashed, it froze, it spat me out. Depleted but with the same obsession, another 20 minutes of frantically clicking passed before I got on the waitlist. Over a dozen times I filled in a “no” on medical background, “vegan” for food, size M for shirt, before the site let me through to confirm my spot. The verdict: #69. Within another 15 minutes the waitlist counted 150 unfortunate ones.

That was not the end of it. Three days later, the race organizer, Aravaipa announced they had reshuffled the waitlist “limbo orders” based on “internal timestamps.” As if that solved the error. A move that felt both opaque, arbitrary, and deeply unfair. I was there trying to register at exactly 11.00, with probably ~400 others, none of it mattered. My waitlist number now: #180. Sigh.

The passing days I witnessed the entrants list grow with 50 new runners. Including high-profile figures like Max Jolliffe and Randi Zuckerberg. Not great optics in my opinion. The lack of any public clarification leaves a vacuum that’s quickly filled with speculation. Thankfully, after persistently messaging, I too was invited to join (on the premise I would add value to the competition having a 5th fastest male finishing time among the entrants). So I’m in. And I’m very grateful. That doesn’t erase what happened, or what it suggests about the sport we love. The essay could have ended here. But this is also about what comes next. What this moment reveals about the state of ultrarunning, and the responsibility of organizers, platforms, and communities.

I am left asking: is this the price of popularity, and what does that cost us?

Cocodona is not just a race to me: it’s my heart and soul in running. Something I cannot just replace with a different 200-miler on a different weekend. From the moment of its inception six years ago I have tried to enter. COVID and injuries limited me to merely one participation. For half a decade I built my schedule, travel, time off, the planning of our wedding, and emotional energy around this event.

I didn’t even make it to the start line, of the signup form. Now that I have, the question lingers: how do we ensure similar future runners can trust that start line will be there for them too? How do we preserve fairness, transparency, and community, as ultrarunning grows beyond its roots?

Where to take this frustration?

It’s fair to ask why this happened. I’m not writing this to pick up pitchforks or start a blame campaign, least of all Aravaipa. This tech failure wasn’t on the organizers. Truly, what they’ve built is remarkable. Cocodona is one of the most iconic, imaginative and meaning-rich events in the world. They’ve done it while staying grounded, supporting Indigenous and other minority groups, raising awareness and money for great causes, and cultivating a culture that many of us want to belong to. That kind of intention and leadership (unfortunately) stands out.

If anything, the chaos behind the scene is a testament to how powerfully they’ve succeeded.

UltraSignup could have (and should have) anticipated this level of demand and server traffic. With the race’s well-known growing popularity, and data to go on, the platform should have anticipated this. Cocodona isn’t a pop-up garage race; it’s one of the premier races in North America. What happened was not a fluke. It was foreseeable, preventable, and frankly, negligent. It is not technically difficult to build infrastructure that can handle a few hundred simultaneous requests. E-commerce websites, ticket venues and race lotteries do this every day (cloud-based load balancing, queue systems, or scheduled staggered rollouts are common practice).

The consequences remain though. As is the feeling that something is very wrong here, beyond the personal agony. My concerns are not with the technical failure, but what this signals for the future of the sport. As ultrarunning scales, so must our standards for transparency, communication, and infrastructure.

What does this mean for the race?

Cocodona is a 250-mile trail and mountain traverse. It’s not a leap; it’s a long-haul odyssey taking most over 100 hours to finish. With the popularity the signup becomes a race of who clicks faster or just is lucky—not who’s ready—and we have to ask what values we are rewarding. 200 Milers used to be the kind of race people worked toward; a culmination of years spent digging that pain cave. That doesn’t seem to be the bar anymore.

I couldn’t help myself from doing some digging. I need to make sense of it all. The numbers point to a structural shift in how athletes are approaching 200+ mile races—particularly Cocodona—and raise important questions about readiness, sustainability, and values. The result is hard to ignore: nearly half the field is stepping into a 250-mile race with minimal experience.1

Out of the 260 entrants for 2026 at registration, 66 have no(!) 100-mile finishes listed on UltraSignup. Another 55 have only one.

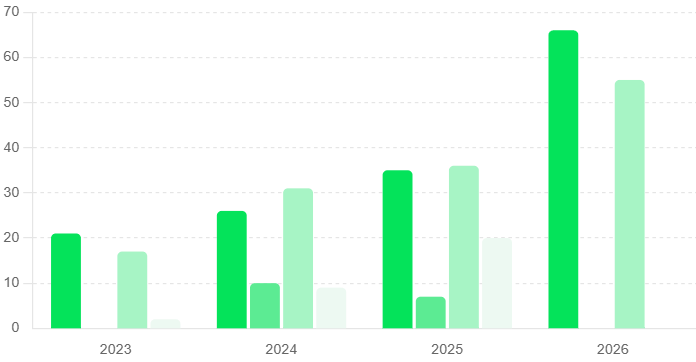

Compare that to: 2023 and 2024, when about 27-28% of runners were similarly inexperienced; 2025, where that number jumped to 33.5%, and: now 2026, with a record-high 47% stepping in without a solid foundation. In just one year, there’s been a 13-point jump in inexperience among entrants. This is not a subtle trend—it’s a sharp increase, with 2026 seeing a 70% rise in relative inexperience since 2024.

If a growing percentage is unable to finish within very generous time limits that should prompt serious reflection. Not because slower or less experienced runners don’t belong—they do—but because it signals a disconnect between the demands and replacing readiness with randomness. Over time, I am convinced, this will erode the spirit and sustainability of events like Cocodona.

⏹ zero 100 mile finishes prior to registration

⏹ completed a +100 mile race after registration

⏹ one 100 mile finishes prior to registration

⏹ completed more +100 mile race(s) after registration

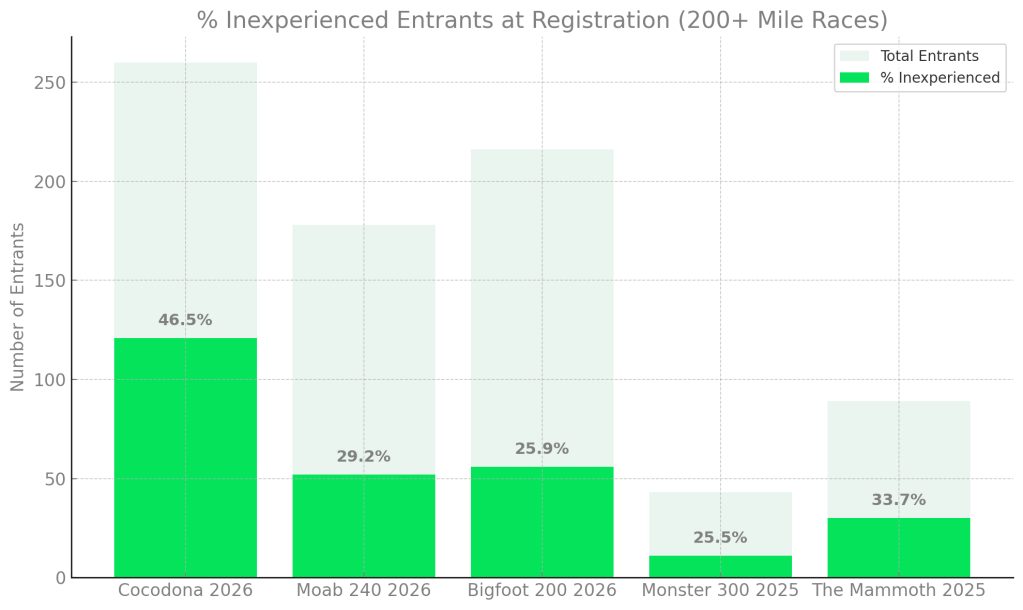

The data paints a clear picture: the barrier to entry for 200+ mile races is eroding, and not necessarily in a good way. Compare the 47% with Bigfoot 200, Moab 240, and even the inaugural Monster 300 and the Mammoth—all US +200 milers with no entree requirements, and a stark difference of participants entering with limited ultra-distance credentials appears.

Of course, not all experience is captured here. Some runners come from different backgrounds or international events. But numbers like these point to a massive shift: from viewing 200s as a pinnacle earned through progression, to treating them like a bold click (based on live stream vibes).

If we want to keep these races inclusive and inspiring without making them soulless or unsustainable, we need to ask what kind of readiness we’re actually rewarding, and what kind of journey we’re encouraging runners to take.

This isn’t about drawing hard lines or excluding eager athletes. I say this because I’ve lived the humility this distance demands. When I toed the line for my first 200-miler, I had already completed seven 100-milers. Still, I felt wildly underprepared—emotionally, logistically, spiritually. When nearly half of Cocodona’s 2026 field may never have run through a sunrise, we have to ask: what is being optimized here?

One possibility is that the barrier to entry has shifted from experience to enthusiasm. While passion fuels much of our community, a growing disconnect between readiness and reward has real consequences, for runners, crews, volunteers, and the very spirit of the sport. The data doesn’t just tell the full story. It signals a choice. The question remains: what kind of future are we building, for this race, for this sport, for each other?

PART 2 continues here.

- I used a deliberately simple metric as a rough proxy for experience. I recognize that this is an arbitrary threshold. Experience is more than finish counts; it’s about time on feet, depth of suffering, self-reliance, et cetera. Some runners gain that in a few big efforts, others take years.

↩︎